Everyone Log Out, I Want to be Alone

The Spectacular Rise (and Fall?) of the Terminally Online Creator-Influencer-Culture-Critic

It’s a Wednesday and one of my fellow creator friends—a catch-all term I despise in some ways, as it has reduced anything of any genre of material that we produce to mere “content”, dispossessing us of other, less commodifiable names for our work like “art” or “satire” or “writing” or just “my actual literal life” perhaps—sends me a Vox profile of a young 20-year old TikToker named Rayne Fisher-Quann entitled “A day in the digital life of an internet it-girl”. Although I had not come across Rayne before, I recognized her story and I recognized myself in it to some degree. She tells the Vox reporter that the first thing she does in the morning is log on and look for fires to put out: “Every day I wake up at 9 am, name-search on social media to make sure everything’s gone well, and then go back to sleep. This is my worst and most obsessive habit. I pretend it’s because of my evolutionary desire to gossip or whatever and not just a symptom of low-grade narcissism.”

It’s not the only place where Rayne self-deprecates or pathologizes her various psychological responses to internet fame. She narrates her own experiences as an awkward tension between being critical of the concept of the “cool it girl” while also clearly feeling attached to her status as exactly that.

I don’t see her first-thing-in-the-morning ritual of scrolling as a sign of narcissism; from personal experience, I think it’s probably a just a very reasonable anxiety. She doesn’t explicitly state that she is looking to do damage control for any potential disasters first thing in the morning, but I have a gut feeling that she is. I often go through the same ritual (on a lesser scale) upon waking, and it’s never something that makes me feel good. Opening my phone in the morning often feels dreadful, it leaves a pit in my stomach because I know how possible it is for something to spin completely out of control overnight online; you never really know if this morning is the morning you’ll wake up to a bunch of horrible comments dragging you and everything you love through the mud. Sometimes your post winds up in the wrong corner of the internet and suddenly your DMs are full of guys threatening to slit your throat or people telling you to kill yourself. If you’re not white or not cis or anything else deemed inferior by bigots, this type of abuse is more frequent and more extreme.

But it’s not just bigots who are eager to be abusive. I think most of us can agree there are many cases of (perhaps well-intentioned) people who decide to take it into their own hands to punish someone online with a lot of followers for every potentially problematic behavior. This occurs, sometimes at extreme levels for even minor mistakes, under the justification that they are causing some vague “harm” to the “community”. Often, it seems as if the scale of the response is disproportionate to the scale of the perceived slight. Whether you agree that “cancel culture” exists or is a problem or not, I think we can all agree that being constantly evaluated by thousands of people who all have different ideas of what is correct or moral is enough to give anyone an anxiety disorder.

The endless surveillance by masses of people holding you to a seemingly impossible expectation of political purity is especially true on woke zoomer TikTok, where Rayne seems most active. So I can’t help but feel bad for her. I worry about how it will impact her (and other young people) over time to have their early lives recorded so publicly considering how much we tend to learn and change in those years between the last gasps of childhood and the first breaths of adulthood. I worry about how being correct from the beginning has become more important than accepting when you are wrong or when there are limits to your knowledge. Is there any room for believing in the possibility of transformation?

Although it might be difficult to understand this if you’ve never been in the position of having a lot of internet attention on you all at once, it can sometimes feel impossible to maintain your own perspective under the constant weight of conflicting external opinions. Now that I am closer to 30 than 20 and greatly jaded with online micro-fame, I can’t help but think that it is somewhat inhumane for very young people to become internet celebrities. While internet celebrity does, for some, translate to an entire career and fabulous wealth (as might be the case with the D’Amelio sisters, for example), internet clout does not lead to happy endings for many “creators”.

Rayne is good at identifying some of the perils of being highly visible, and therefore highly commodifiable. She has frequently declared her desire to avoid exploiting the parasocial relationships between her and her followers for the sake of becoming a salesperson for some company; even her Tiktok handle, @_raynecorp, is a satirical reference to the importance of rejecting corporatism. Rayne has declined to become a mouthpiece for major corporations thus far despite strong temptations, according to her substack: “real, major brands started offering me real money to convince my beloved followers to buy their shit—and in case you didn’t know, the amount of money that companies will offer even the most mid-tier social media users is, respectfully, an insane fucking shitload. four. figures. three zeroes. Jesus.”

I admire her rejection of the complete commodification of her personality, which is, for the record, exactly what monetized “creators” are doing most of the time. That’s why it feels like “selling out”. There is a real tension here for both creators and audiences because the introduction of some external company speaking through popular internet micro-celebrities also introduces the potential of disingenuousness.

The real product that audiences want to consume is the illusion of authenticity because it simulates intimacy with the creator. Buy this and you can have a personality like me; you could be a person who could be friends with me. It’s obvious why many find it distasteful for popular internet personalities to use their likability to sell stuff. It seems to go directly against the internet ethos of an alternative media ecology, an organic cultural environment, as opposed to the highly produced and staged Hollywood productions we are used to seeing. After decades of reality TV being the most popular entertainment format, it is unsurprising that we have developed an entire digital culture in which the primary goal is the transformation of life into “content”. Highly visible internet beings are reality entertainment. POV: a day in the life of ____.

Despite many cliches about how “what you see online isn’t real”, we still become irritated when the illusion of authenticity is broken by the incursion of capitalist advertising through the mouths of our favorite people. It’s frustrating enough when the Kardashians peddle fast fashion or hair vitamins to audiences who don’t realize they’re being sold a cult of personality and not a product; it’s downright dystopian when teenage TikTokers start doing it.

Yet, as I can attest from personal experience, it can develop into a necessity. The reality is that social media is designed to extract free labor and then monetize it for the platform—not the creator. Social media companies capture our free labor and our intellectual property, and we have to figure out ways to make up for that theft somehow if we want to justify the amount of time and energy we invest. It would cost TikTok or Instagram billions of dollars—uncountable fortunes—to pay for their platforms to be populated with enough media to keep eyes glued to screens the way they are now. Television and film require sprawling budgets to fill up the screen time between advertisements; social media content generally does not. We, the masses, eagerly do that labor for corporations because self-publishing does provide us with an illusion of autonomy. But how much autonomy do we really have when anything we do online becomes commodifiable, sellable? Are we being dispossessed of our actual autonomy through the pursuit of the illusory autonomy of celebrity?

The majority of successful “creators” I know generally spend hours and hours online every single day just maintaining their pages and producing material for them. Of course, one might eventually develop the optimistic (if unrealistic) aspiration to be compensated—if not because you believe in grinding and hustling, then because you can’t work some other job during the time you’re investing in your platform. And, honestly? Many aspects of running an online page are not fun. It is not fun to have tens of thousands of people constantly demanding free access to you, yelling at you like you’re not a person for any perceived wrongs or slight failures, treating you as if you’re a brand and not a person. Do better, they say.

To some degree, it’s understandable that audiences view us as brands because many of us are turning ourselves into brands, either intentionally to make more money or unintentionally as the effect of absorbing the culture of compulsory self-branding. But it’s also deeply, deeply unfair to conflate individuals with being brands, especially when we are not equipped with the resources of real brands—resources like, for example, PR teams who can handle a nasty comments section for you if you’re having a meltdown from too much constant negative feedback, or a legal team who can protect you if your intellectual property gets stolen and monetized by someone else. It’s hard not to think of the assholery happening over at Doing Things Media, a corporation that runs some of the most popular meme pages on Instagram that, importantly, do not credit or pay most of the creators they take content from. Monetized repost pages like these leave a nasty taste in the mouth of anyone churning out content for free online.

The combination of theft of labor value from the platform itself, and from bad actors on it, creates a feeling of—well, if companies are going to steal my shit and make money off of it, and if running this platform is going to require massive amounts of my time/emotional energy and possibly destroy my mental health—then I might as well make some money myself. If this thing is going to take over my entire life, I need to figure out how to make a life out of it. It might feel to some audiences like the micro-fame and social capital is the reward itself, and that actual monetization that is somehow morally bereft; but, people who think in this way often do not have the experience necessary to understand what a raw deal many creators are getting. Our content is so valuable, and yet most of us get nothing. No matter how flashy and cool it might look (or feel) to have a big account, it comes at the cost of your privacy and your labor.

It would feel more acceptable to put that much time and energy into our own pages if they truly remained our own pages. But they don’t. Once you gain a certain amount of attention, your page stops belonging to you alone. People who follow you start to feel entitled to your time, your ideas, your individual attention. They get angry if you post things they don’t agree with. They think it’s their responsibility to police you, even put you in your place, purely because they follow you—because they’re giving something to you, right? And so you must owe them something in return, even if you never asked them to follow you in the first place; this is where that pesky word “community” comes into play as a form of entitlement. While I won’t go into that tangent here (maybe another time) the phrase “community” has been so twisted online as to be an essentially meaningless signifier that just stands in place for abstract entitlement. Once the people who follow you decide that you are a “community”, you suddenly have an obligation to them.

The plain truth is that our monkey brains were not designed to handle this level of social feedback, positive or negative. It invariably warps your perspective to have tens of thousands, millions of people following you. You are a concept to people—a placeholder for adjacency to fame, popularity, coolness; or a placeholder representing some ideology or practice that people don’t like, and therefore you are the “right” target for vitriolic rebukes. Or, as a friend of mine satirized it, the common accusation that some minor detail has been left out on purpose in order to harm people or because the person behind the page is themselves a bad person. You did not mention this other thing, probably because you are violent. Hearing that kind of thing day in and day out will eventually shut your brain down to criticism, as it becomes difficult to differentiate real criticisms from disingenuous ones in a hyper-reactive web culture.

Depending on the context, some creators who respond to this negative feedback by becoming block-happy or just ignoring criticism altogether are being reasonably self-protective. While it is important to hold power to account, someone having a following does not necessarily mean they have power and we, as individuals, are allowed to be flawed and make mistakes just like anyone else. The fact that people think it is okay to surveille anyone with a larger following to the point of collecting constant “receipts” on anything they do, all the way down to offenses such as liking a post from someone deemed “problematic” for some long-ago offense that nobody can really remember the specifics of (but don’t worry, I’m sure it’s true, someone posted a call-out two years ago and one time in a comments section a stranger called them ableist without specifying why).

In short, it’s a clusterfuck. In gaining an internet following, you’re also gaining a lot of risk. Risk of having any squabbles you have with others (or, god forbid, a breakup) being made into a public spectacle of entertainment. Risk of having your real location, identity, job, school, family members’ names, hell even your height and shoe size, made into public information. Risk of having no way to become just a person again; once you reach a certain level of virality, there’s really no point at which you can ever go back to being a “nobody”—something many of us desperately desire after becoming somebody and finding out it isn’t all it was cracked up to be. And, throughout all of this, you get none of the protections afforded to traditional media celebs; no PR team to defend your name, no security detail to protect your home, no legal team to trademark your intellectual property. Nor do you even get the stability and comfort of a real income, at least not without “selling out”.

Enter stage left: a quickly growing genre of intellectualized quasi-professionals who have found a way to make money without ceding their autonomy to external corporations. I’ll refer to this loose bunch of people as the creator-influencer-culture-critic (or influencer-essayist, as Vanity Fair has called Rayne) group. These are creators who, for some reason or another, decide to use their social media platforms and their parasocially bonded audiences to build up alternative publication careers more aligned with what we have traditionally seen from institutionally supported journalists or academics.

Of course, we have had some variety of this on YouTube and in podcasts for some time now, but the genre seems to be rising on TikTok and Instagram at the moment—which is notable specifically because these platforms are typically less conducive to longer form discourse. As primarily visual platforms, they seem to encourage the development of a more highly performative and aestheticized influencer culture when compared to other more text-friendly social media platforms. The text emphasis on Twitter is likely a big part of why journalists and other writers tend to prefer it compared to Instagram.

Some of these creator-influencer-culture-critics are academic writers who have become disenchanted with the trappings of academia, whether due to a lack of decent wage opportunities or due to elitist cultures. However, most members of this group are autodidacts, or self-educated intellectuals. They utilize a broad variety of approaches to publication, from publicly accessible platforms like Substack/Medium, to subscription formats like Patreon essays, to hybrid formats like podcasts that generally have both free and paid access options. Some have even transitioned into writing actual hard-copy books, often using their social media platforms to crowdfund the self-publishing costs.

Joshua Citarella and Brad Troemel inevitably come to mind, each having used their skills as academic cultural critics to build an array of platforms from Patreon to YouTube to Instagram to Twitch streams (and, in one case, even attempts to launch an independent publishing platform and a line of NFTs, which I will, with a disapproving glance, keep my mouth shut about for now). We also see people like MJ Corey gaining lots of attention for her cultural criticism over at @kardashian_kolloquium, but expressing frustration at her seeming inability to have her work taken seriously enough to transition into mainstream publications (at least that was the case before her writing suddenly began appearing on Vogue’s site). On the other hand, we have someone like Taylor Lorenz, who seems to have made a transition in the opposite direction—going from New York Times tech reporter to a quasi meme influencer on Instagram/Twitter (as well as a Washington Post reporter as of recent). Of course, Twitter also has an entire massive community of celebrity-style academics and journalists who tend to publish in both mainstream and independent formats.

Then there are those who have achieved online intellectual authority without achieving traditional institutional endorsement first. Jesse Meadows, also known as @queervengeance, is one of those people. Although they began their account as a meme page just for fun, their scope has grown over the years into an impressive body of critical work published on Medium, Patreon, and in their own independently produced formats, including a newsletter called Sluggish, some YouTube videos, and a podcast called Disorderland that is co-hosted by another prolific author, Dr. Ayesha Khan aka @wokescientist (whom I have recently collaborated with on a series about digital culture and surveillance capitalism; you can check it out on Substack here). Jesse spent years chronicling their self-education in the philosophy of neurodiversity, frequently publishing informal book reports and annotated readings to their Instagram story, or distilling important findings from scientific studies into memes and graphics.

In our private conversations, Jesse has commented that successfully transforming their platform into a sustainable career (without losing their mind or selling out to an external corporation in the process) came at the expense of meaningfully disengaging with social media. They take frequent, weeks-long breaks from Instagram and they no longer answer DMs or scroll comments; they tell me people are usually more measured with criticisms written out over email, as compared to the reactive anger of IG story responses or Twitter replies; they garden a lot. Looking at the calm success they’re having while pursuing and financing their own interests—all without having to embrace the identity of “influencer”, a term which they certainly would reject—it’s hard not to think to myself that maybe they’ve got it all figured out and the rest of us should take heed.

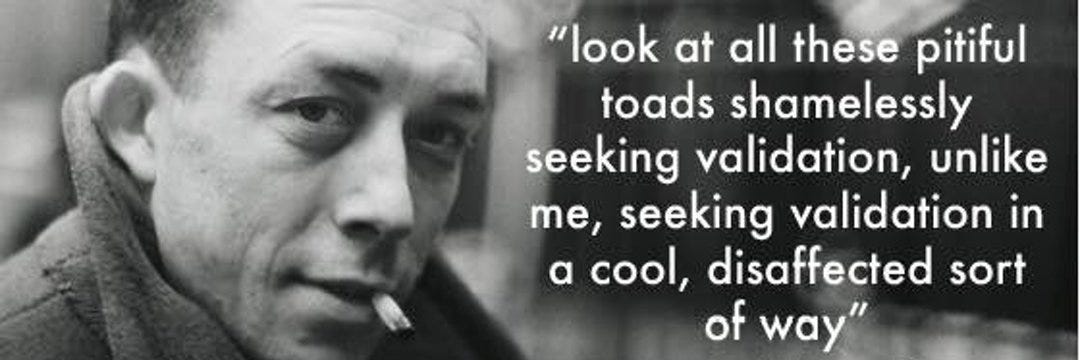

In my experience as a humble meme creator, trying to stop being an internet personality after you become one is kind of like trying to stop smoking. You know that cigarettes are bad for you, you’ve read all the studies, and you bitch about it and get mad at yourself every time you smoke one. Yet you just keep smoking and smoking and smoking; and maybe glamorizing and aestheticizing it—looking really cool while doing it—helps you justify the self-harm a little bit. Maybe it’s okay that looking cool comes with risk. Maybe it’s okay that it causes damage. I can’t help but think about 20-year old Rayne Fisher-Quann’s (now former) Twitter header:

Maybe Rayne is right that it all comes back to narcissism and shameless self-promotion, even if those things wind up being destructive to one’s emotional wellness. Maybe it all comes back to grind culture and the feeling that you have to turn your hobby into a hustle, even a career, within this capitalist hellscape. Maybe it’s just the next stage of compulsory self-branding and self-commodification. Maybe some people just want to be wealthy and important. I’ve also written (in my essay collaboration with Dr. Khan) about Tiqqun’s theory of the self-commodifying Young-Girl who continuously makes the values of Empire (the dominant culture) trendy in order to be deemed worthy in the eyes of the Spectacle.

I think the role of the creator-influencer-cultural-critic arises out of the desire of the real people behind the platforms to reclaim their autonomy from the whole self-objectifying influencer framework itself. To use their clout for more than just funny pictures with words or repeating the same TikTok dance over and over. Maybe it is a role that rewards people for developing themselves more as readers, writers, and intellectuals. Maybe independent platforms are an escape from the hell of the comments section or the DM request folder specifically because they don’t grant direct, immediate access to just any stranger who comes across a post they don’t like. Maybe, theoretically, this is the best way to make sure you’re able to say what you want to say on your own platform, and to avoid being the mouthpiece for some company trying to sell something you don’t care about.

Yet, the market becomes more and more saturated every day. It seems like twice a week I see a new Patreon or Substack or virtual seminar launched by a fellow meme page admin on Instagram (although, to be fair, I do gravitate towards a particularly intellectualized digital microculture populated mainly by leftist propagandists and “theorygrammers”). It’s a little nerve-wracking to invest so much energy in alternative platforms for your work without knowing whether or not it will pay off in the end.

The question of what role “creators” are supposed to have, what our motivations should be, and what it means to be a creator in the “right way”, is hardly even a coherent question—so I’m not sure why people seem to think there’s some kind of correct answer. Truth always inhabits the gray areas between black and white, and we are all just trying our best to survive the slow shock of our real lives being turned into a spectacle. It does affect you emotionally when you realize that people want to consume your personal life as much as, if not more than, they want to consume your “content”.

For now, I have no advice other than this: each one of us, whether we have five followers or five million, needs to be thinking a lot more critically about how blurred and twisted the dynamics of private and public life have become in the era of social media. And we need to be more respectful of each other’s right to have a private life, no matter how public and terminally online someone might seem. Random strangers are not entitled to consuming every waking moment of your life as content just because they chose to follow you on a website.

All that being said: feel free to subscribe to my Substack (free) or Patreon (paid). Yes, it is a little joke to promote my paid platforms at the end of an article all about the dangers of monetizing your platform, but also, no it’s not a joke. As I’ve stated many times before: everything is a joke, nothing is a joke, and I can’t be killed.

The long story short is that I’m not trying to abuse parasociality here, but I do have well-informed opinions and lots of bills to pay—and I don’t feel like leasing out my voice to some corporation trying to sell shit. A little tip for my efforts would really help a guy out. Hope you can understand.

love,

sprank

—

If you’d like to financially support my writing or access more exclusive content, including my PDF library, reading guides, podcast episodes, playlists, forbidden memes, and other goodies, follow me on patreon + check out my heinous merch. Or you can buy me a coffee instead <3

like im gonna buy u a faggot, cofeee